Red Coats and All

A Little bit About Tommy Atkins

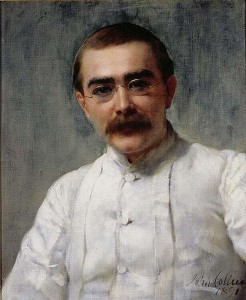

With the passage of Empire the writings of Rudyard Kipling have certainly today taken on the air of debate. Created during an age when the pink of world globes symbolized the far reach of Queen Victoria, her soldiers and her little wars, Kipling’s work is a symbol of Britain and Empire.

Though no great critic of literature, as I tend to devolve myself from the non-mercy of passing years and instead attempt to understand the work for what it represented in its day, I find myself turning to Kipling’s work as a record of his thoughts; a man with pen perhaps musing for himself and his public. For myself, I would rather become engaged in learning more about this age of Kipling, reading, studying, or discovering more about the antagonist in Kipling’s work, the men who fought against the realm. As I sit here in quiet contemplation images pass through my mind and I can see Plummer, Connery and Caine, “The Man Who Would Be King” (1975), Stockwell, Flynn and Lukas in “Kim” (1950), and Grant, McLaglen, Fairbanks Jr. and Jaffe in “Gunga Din” (1939).

Then there is “Tommy”, the title of the British military historian Richard Holmes’ book on the British Great War soldier. The name Tommy is a well-known nickname of that Great War (1914 – 1918) solider whether he came from Devon or Northumberland, Liverpool or Bath, London, Hastings and so on. Tommy is derived from “Tommy Atkins” and the nickname may have its origins as early as 1743.

In 1892 Kipling’s ode to the British soldier, “Tommy” was published. This personal dialogue of one Tommy, one Tommy Atkins is cumulative in its discussion of the British soldier that defended Empire. Kipling’s soldier was the Tommy of the Crimea, the Indian Mutiny, Abu Klea, the Sudan, the Dargai Heights and elsewhere; wherever Britain’s colonies sat amongst the pink, and wherever the Empire was under threat.

Tommy’s opponents were often the locals, the ones whose lands the British occupied, opponents who challenged that age of Empire whether intentionally or not. These men, the Zulus, the Boxers, Pathans or the Boers, and so many others have become the focus of many – from professional historians to armchair generals, the museum, the re-enactors, the specialist and generalist. There are those among us who are resplendent in their knowledge of these times; knowledge of each ridge, each river, sabretache or badge, weapon or foe, and Tommy Atkins himself, red coats and all.

Did you know?

Rudyard Kipling’s son Lieutenant John “Jack” Kipling (Irish Guards) was killed in 1915. After the war ended Rudyard Kipling was asked to work with the Imperial War Graves Commission, now the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, providing his pen for the needs of the commission.

Kipling penned, for the Stone of Remembrance in Commission cemeteries, “Their Name Liveth For Evermore” (Ecclesiasticus 44:14), and for the graves of the unidentified, “A Soldier of the Great War Known Unto God”. Kipling is also credited with coining the phrase “Builders of Silent Cities” for the War Graves Commission’s Masonic Lodge.

A film entitled “My Boy Jack” with David Haig as Rudyard Kipling and Daniel Radcliffe as John Kipling was produced for television in 2007. The film is based on Haig’s 1997 play of the same name which comes from Rudyard Kipling’s poem about his son and entitled “My Boy Jack”.

Comments